When Risks Outweigh the Impact of Global Health Trips

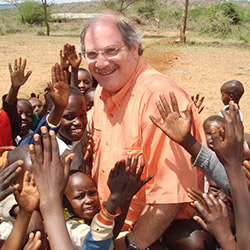

David Beyda, MD, has witnessed natural disasters in Haiti, bombings in Gaza and genocides in Cambodia. He went into medicine to help the greater good, which led him to global health where he could help patients on an international level.

As an ethicist and global health pediatrician, Dr. Beyda sees the world differently than most physicians. After more than 50 global health trips that left him feeling an array of emotions, Dr. Beyda began to recognize the risk of these trips, and how sometimes the risks outweigh the impact.

Dr. Beyda discussed his life experiences, passion for global health and the risks of international travel.

He began his presentation by posing this question to the audience: “Is the risk you’re taking by traveling worth it?” Risk is not just emotional and physical harm, but involves virtue, self and family, he said.

According to Dr. Beyda, a virtuous individual is kind, makes sacrifices and comes to the aid of those who need help. Often, physicians go on global health trips under the pretense of virtue only to find out that it backfires. When doctors think of virtue, they think about what they should do. Most doctors believe that if they deny that obligation to their profession, then they are denying their moral obligation to help others.

“We need to be aware when virtue becomes self-serving,” he said. “When it has that feel-good effect, that’s when we are in trouble. We have to be realistic about the reason we want to go.”

Dr. Beyda said it’s easy for medical trips to become self-serving when a physician comes home and says, ’Look what I’ve done, look at who I am.’ “This is the time where you need to have your hand slapped and be told ‘No, this is not about you.’ ”

When trips become self-serving, it gives physicians a feel-good rush, but perhaps it shouldn’t, he said. “When you are virtuous to those who come to you for help, maybe you’re supposed to feel sad. Maybe you need to feel helpless and concerned.”

Being self-serving can lead to short-term benefits, he said. Imagine going to a new country, giving 1,000 kids worm medication, vitamins and education about good hygiene practices. After a week, you leave and those kids return to their normal routine with no medication, no vitamins and dirty water. “That’s not being virtuous, that’s being unrealistic about your impact and the risk that you are taking,” he said.

Dr. Beyda shared a few stories from some of the countries he has visited, offering examples of whether the risk was worth it and whether an individual’s work truly makes a difference.

Cambodia

When Dr. Beyda was a third-year pediatric resident in 1979, he was invited by the International Rescue Committee to lead a pediatric ward at Khao-I-Dang, a Cambodian refugee camp. This was during the Cambodian genocide that was carried out by the Khmer Rouge regime.

Dr. Beyda arrived at the refugee camp in December. They could only care for 100 children at a time, plus families. By March, there were 160,000 refugees in the camp. The team had minimal supplies, could only do one X-ray per week and had one oxygen tank.

“Trying to resuscitate with what we had didn’t work,” Dr. Beyda said. “We had nothing. To make matters worse, the Khmer Rouge infiltrated the refugee camp. At night, you could hear the screams and killings, and we couldn’t do anything about it, and we knew we were at risk.”

Dr. Beyda said he was sharing his stories because he wanted the audience to understand how taking a risk without considering the effect on family and how seeming to be a god-like figure could backfire. “I left angry and wound up being extremely cynical. This was not virtue, this was not self. I destroyed myself from that perspective.”

The Gaza Strip

“Was it worth the risk? We knew it’d be dangerous,” Dr. Beyda said. “We went on the pretense of virtue, but realistically, it wasn’t going to happen. So why take the risk? On a personal note, I was a guy in a white coat seeking a humanitarian award. That’s the danger that took me a long time to realize.”

Haiti

Within 72 hours after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, Dr. Beyda put together a medical team. When the team arrived, there was nowhere to park the plane. There were so many humanitarian groups coming to Haiti that they parked it on the taxiway.

"What was the virtue behind us? It was the split decision that we had to go,” Dr. Beyda said. “We were one of 700 groups that arrived in Haiti. Was it worth the risk? Did it make a difference when we left? To be honest, I don’t know. Did we rescue people? Yes, of course we did, but so could the other facilities. I keep coming back to this risk assessment and the three other components that are so important: virtue, self and family.”

Dr. Beyda said he wishes someone discussed these components of risk with him and asked him these questions before entering the global health profession. He hopes students will learn, just as he did, the impact and consequences of these global health trips.

“We left behind an intent to help,” Dr. Beyda said. “Every decision we make is going to have a consequence and we have to own it. We have to remember, it’s not what we bring, it’s what we leave behind.”

When asked when it is worth the risk, Dr. Beyda said this could only be answered with humility and self-reflection. “Look at yourself in the mirror and ask, ‘What do you see,’ ” he said. “Then realize that the real question you should ask is ‘Who are you? A god in a white coat, or a servant to those who come to you for help.’”

About the College

Founded in 2007, the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix inspires and trains exemplary physicians, scientists and leaders to advance its core missions in education, research, clinical care and service to communities across Arizona. The college’s strength lies in our collaborations and partnerships with clinical affiliates, community organizations and industry sponsors. With our primary affiliate, Banner Health, we are recognized as the premier academic medical center in Phoenix. As an anchor institution of the Phoenix Bioscience Core, the college is home to signature research programs in neurosciences, cardiopulmonary diseases, immunology, informatics and metabolism. These focus areas uniquely position us to drive biomedical research and bolster economic development in the region.

As an urban institution with strong roots in rural and tribal health, the college has graduated more than 1,000 physicians and matriculates 130 students each year. Greater than 60% of matriculating students are from Arizona and many continue training at our GME sponsored residency programs, ultimately pursuing local academic and community-based opportunities. While our traditional four-year program continues to thrive, we will launch our recently approved accelerated three-year medical student curriculum with exclusive focus on primary care. This program is designed to further enhance workforce retention needs across Arizona.

The college has embarked on our strategic plan for 2025 to 2030. Learn more.