Study Shows Isolated Brain Injuries Cause Lung Damage

A study led by researchers at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix showed that an isolated traumatic brain injury (TBI) directly damages the lungs within an hour of injury.

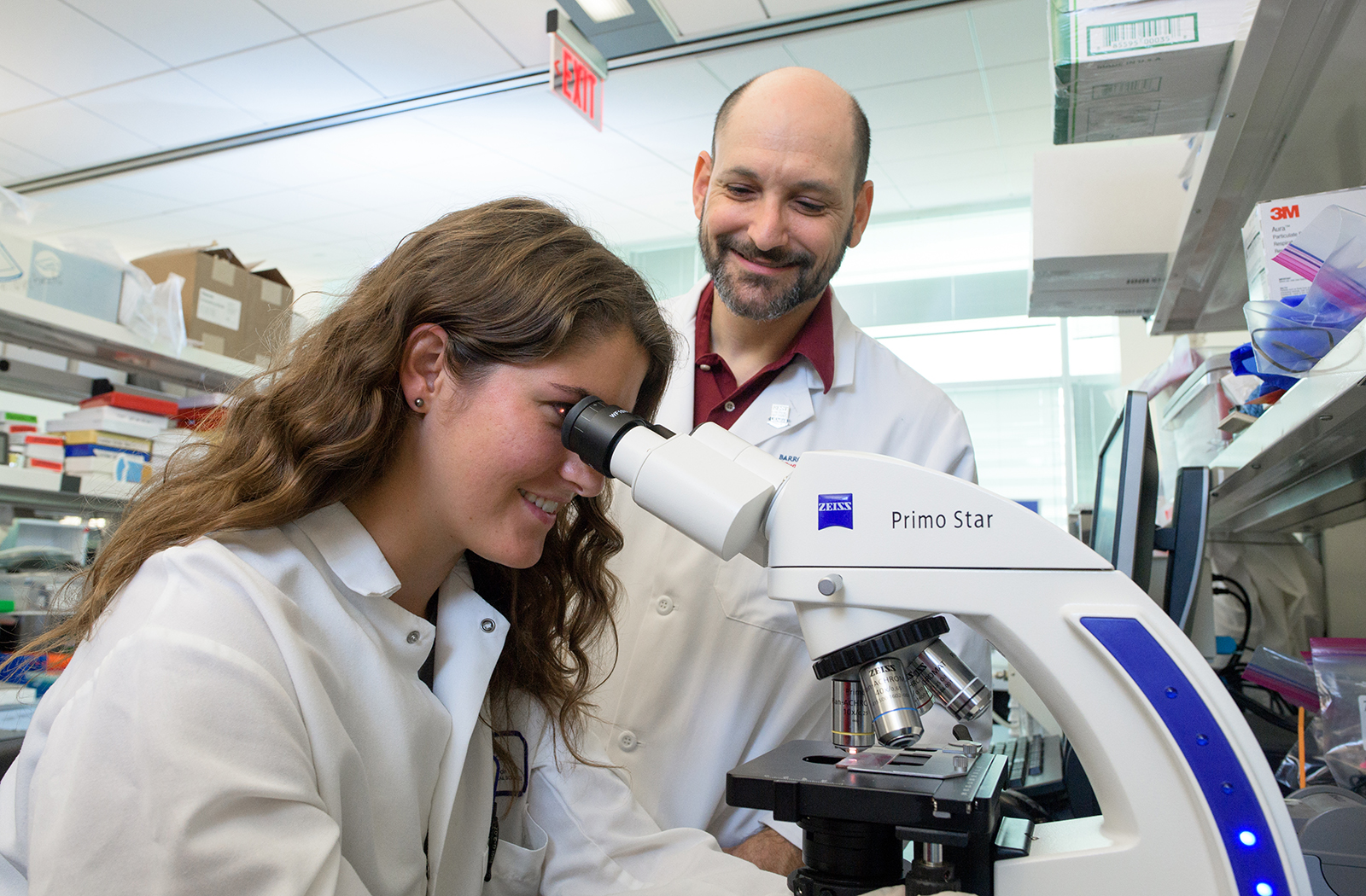

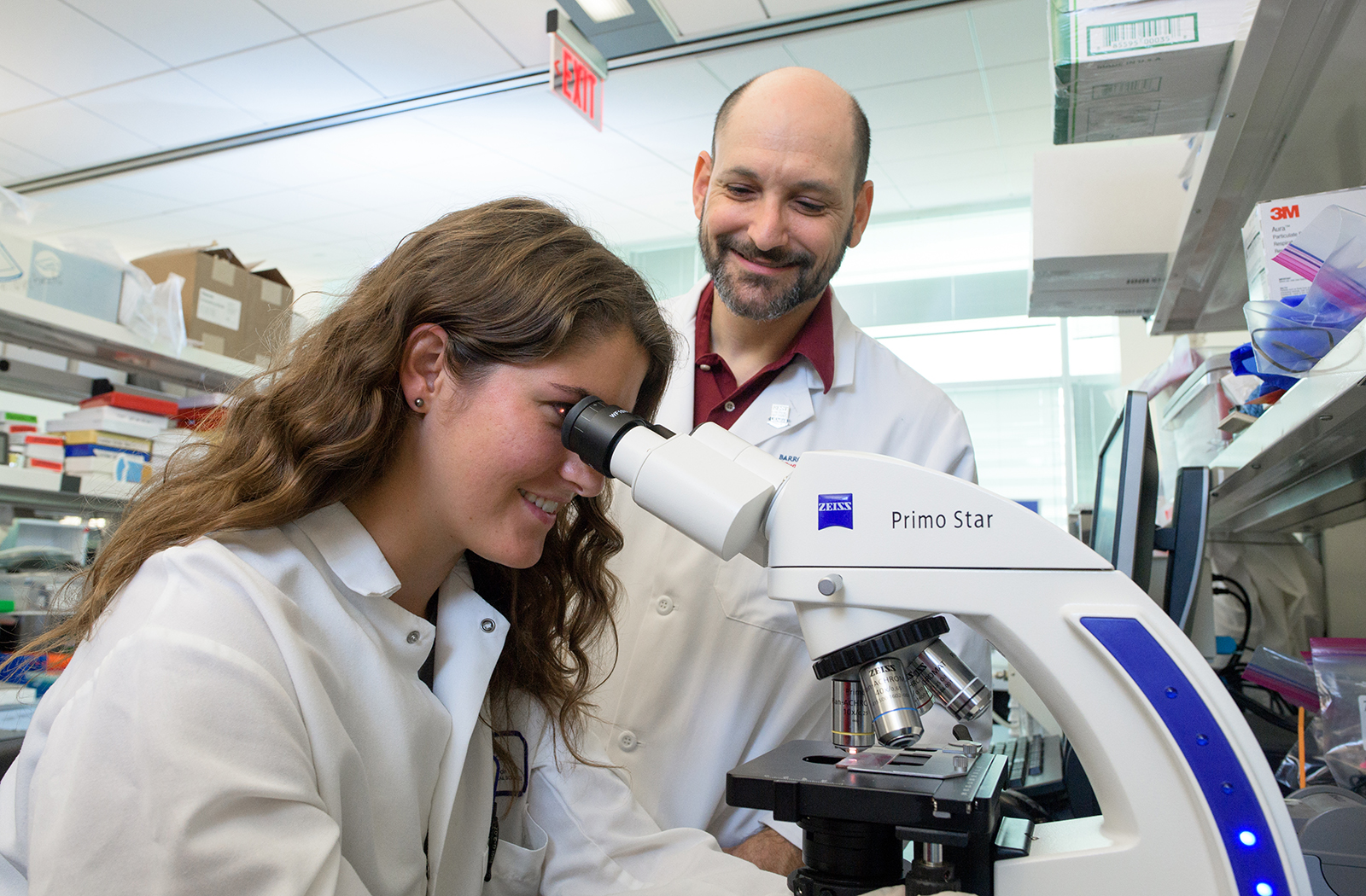

Collaborative research from the laboratories of Jonathan Lifshitz, PhD, director of the Translational Neurotrauma Research Program, and Ting Wang, PhD, scientific director of pulmonary and endothelial research at the College of Medicine – Phoenix, was published in August 2020 in the journal Shock.

“Few other studies have looked at this phenomenon, and we are the first to confirm that it happens in this model of TBI. Furthermore, clinical data suggest that TBI patients are likely to die of pulmonary-related issues and the survivors that develop a lung injury after a TBI have poor outcomes and reduced quality of life.”

Through this study, researchers modeled the phenomenon by which factors associated with TBI hold the potential to damage other organs. Further, the research outcomes showed that the non-invasive intervention of remote ischemic conditioning (RIC) reduced lung injury and evidence of inflammation. RIC is the repeated use of a blood pressure cuff to generate intermittent reduction of blood flow to a limb. Others have demonstrated clinical efficacy to reduce inflammation and prevent damage to organs during heart attacks, strokes and organ transplants. The U of A team provided evidence that RIC may reduce inflammation by releasing irisin, an anti-inflammatory protein released from the muscle usually during exercise. They also provided evidence that the lung injury that occurs after TBI may be due to some dysregulation of receptors associated with sphingosine 1- phosphate (S1P), a molecule necessary for healthy blood vessels in the lung.

Dr. Saber added that although it’s not very well-known that an isolated TBI can lead to acute lung injury, their major contribution to the field with this study is that RIC could be used to prevent or reduce lung injury associated with TBI. Since RIC is relativity inexpensive, easy to use and non-invasive, it can be performed rapidly after a TBI or in cases where TBI risk increases (e.g. players before a football or soccer game) and help improve outcomes for these patients.

“A TBI-induced lung injury is something that has been established before, but it is still not common knowledge or commonly researched,” Dr. Saber said. “RIC has been used to treat lung injuries before, but no other studies have put the two together yet. We are looking to replicate the laboratory data on lung injury and evaluate a treatment that could be applied in the pre-hospital setting – such as an ambulance or urgent care.”

The Translational Neurotrauma Research Program has studied RIC interventions for other aspects of TBI, including inflammation and cognitive deficits. They had observed that their experimental model of TBI resulted in pulmonary edema. With the expertise of Dr. Wang, they evaluated aspects of acute lung injury, including cellular mechanisms of injury and functional preservation. These results demonstrate the complexity of TBI beyond the brain, which encompasses the specific demographics of each patient and their environment.

“As research focuses on providing the evidence for clinical decisions to improve outcomes, it is critical to conduct a comprehensive review of systems with every patient,” Dr. Lifshitz said. “Our results add evidence to attend to the pulmonary system after a TBI and consider the potential for the RIC intervention to promote lung function. In the current environment, we’re all more sensitive to information about lung function because of SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID epidemic that compromises lung function. Risk and incidence of TBI remains high and pulmonary function must remain a priority in the clinical care of TBI patients.

This study, in part, has been presented at several national and regional conferences in 2019. Dr. Saber gave a short oral presentation at the National Neurotrauma Society. Dr. Saber’s undergraduate student, Immaculate (Eden) Christie, presented a poster at the same conference in Pittsburgh, PA (July 3, 2019). Christie presented the work at a few smaller regional conferences including at Phoenix Children’s Hospital (May 8, 2019) and at the AZBio Awards (October 19, 2019). Amanda Rice, PhD, the lab manager in Dr. Wang’s laboratory presented this work at the Shock conference in Coronado, CA (June 8, 2019).

Topics

About the College

Founded in 2007, the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix inspires and trains exemplary physicians, scientists and leaders to advance its core missions in education, research, clinical care and service to communities across Arizona. The college’s strength lies in our collaborations and partnerships with clinical affiliates, community organizations and industry sponsors. With our primary affiliate, Banner Health, we are recognized as the premier academic medical center in Phoenix. As an anchor institution of the Phoenix Bioscience Core, the college is home to signature research programs in neurosciences, cardiopulmonary diseases, immunology, informatics and metabolism. These focus areas uniquely position us to drive biomedical research and bolster economic development in the region.

As an urban institution with strong roots in rural and tribal health, the college has graduated more than 1,000 physicians and matriculates 130 students each year. Greater than 60% of matriculating students are from Arizona and many continue training at our GME sponsored residency programs, ultimately pursuing local academic and community-based opportunities. While our traditional four-year program continues to thrive, we will launch our recently approved accelerated three-year medical student curriculum with exclusive focus on primary care. This program is designed to further enhance workforce retention needs across Arizona.

The college has embarked on our strategic plan for 2025 to 2030. Learn more.