Researcher Seeks to Prevent Heart Failure after a Heart Attack

Heart attack survivors are at greater risk of developing heart failure, a chronic condition in which more than half of those diagnosed will die within five years.

In response, researchers at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix are attempting to prevent heart failure after a heart attack with a novel treatment that targets fibroblasts, cells in connective tissue that produce collagen and play a critical role in healing. An over-production of collagen, also known as fibrosis, is common in people with heart disease.

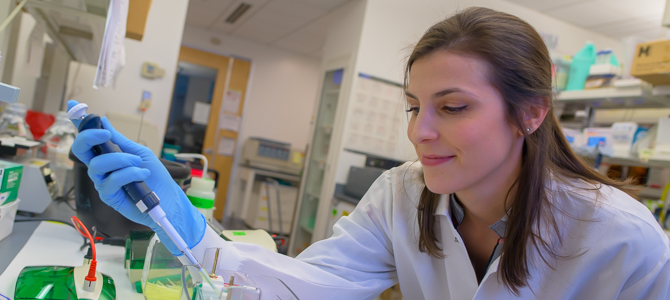

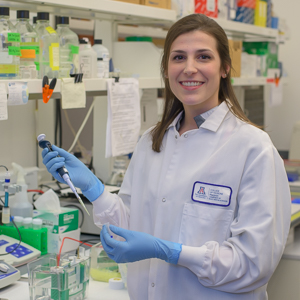

Alexandra Garvin, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Taben Hale, PhD, an associate professor in the Basic Medical Sciences Department at the UA College of Medicine – Phoenix, received a $100,000 fellowship from the American Heart Association in January to understand the influence of fibroblasts and fibrotic signaling on cardiac healing after a heart attack.

Nearly 5 million Americans are living with heart failure. Heart attack victims younger than 75 years old will have about a 25 percent chance of developing heart failure.

ACE inhibitors, commonly used anti-hypertension drugs that lower blood pressure, are effective in limiting cardiac fibrosis following a heart attack. Dr. Garvin’s studies will evaluate fibroblasts in the heart and in isolation to determine how ACE inhibitor treatment impacts inflammatory and fibrotic signaling — and ultimately cardiac healing — after a heart attack. She hopes her research will reveal a greater understanding of the cells that mediate fibrotic responses in the heart.

“Currently no drug treatments are available that are specifically designed to treat fibrosis. Targeting the cells responsible for collagen production and deposition represents an ideal and novel treatment approach,” Dr. Garvin said. “Identifying whether cardiac fibroblasts contribute to the extent of pro-inflammatory signaling, in addition to fibrosis, may increase the ways in which we can intervene pharmacologically to reduce the incidence of heart failure and produce a healthier population of individuals recovering from a cardiac event.”

Approximately 1.5 million heart attacks and strokes occur every year in the United States, according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. They typically happen suddenly when one of the arteries leading to the heart becomes blocked. On the other hand, heart failure is a chronic progressive condition, which occurs when the heart muscle is unable to pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs for blood and oxygen.

“Many positive effects of ACE inhibitor treatment on cardiac injury are due to treatment during and/or after the cardiac insult. Therefore, our research is unique in that the ACE inhibitor is transiently administered prior to a heart attack,” Dr. Garvin said. “Our goal is not to use this approach as a treatment, but rather a tool to understand cardiac fibroblasts. We have shown that this transient treatment leads to persistent changes in cardiac fibroblast physiology that improves inflammatory and fibrotic responses to injury. It is these changes that we are interested in. If we know what alterations in the fibroblast allow for improved outcomes after a heart attack, then this can help elucidate therapeutic targets for future development of treatments.”

About the College

Founded in 2007, the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix inspires and trains exemplary physicians, scientists and leaders to advance its core missions in education, research, clinical care and service to communities across Arizona. The college’s strength lies in our collaborations and partnerships with clinical affiliates, community organizations and industry sponsors. With our primary affiliate, Banner Health, we are recognized as the premier academic medical center in Phoenix. As an anchor institution of the Phoenix Bioscience Core, the college is home to signature research programs in neurosciences, cardiopulmonary diseases, immunology, informatics and metabolism. These focus areas uniquely position us to drive biomedical research and bolster economic development in the region.

As an urban institution with strong roots in rural and tribal health, the college has graduated more than 1,000 physicians and matriculates 130 students each year. Greater than 60% of matriculating students are from Arizona and many continue training at our GME sponsored residency programs, ultimately pursuing local academic and community-based opportunities. While our traditional four-year program continues to thrive, we will launch our recently approved accelerated three-year medical student curriculum with exclusive focus on primary care. This program is designed to further enhance workforce retention needs across Arizona.

The college has embarked on our strategic plan for 2025 to 2030. Learn more.