Bringing Discoveries to the Patient’s Bedside

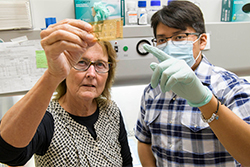

As a visiting professor at Stanford University in the 1980s, Anne Cress, PhD, worked alongside mentors whose findings in DNA replication earned the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and who continued making discoveries at biology’s ground floor. It was in this electric atmosphere that Dr. Cress found her calling, exploring how cells communicate through protein signals.

“That blew me away, that you could change a cell’s fate by changing what signal it got, something that binds onto the surface and tells that cell what to do,” Dr. Cress recalled. “I got hooked.”

Now a professor of cellular and molecular medicine and vice dean of operations and strategy at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Tucson, Dr. Cress remains fascinated by how cells receive and act on biochemical messages. Her focus has narrowed to cell receptors called integrins, which relay instructions to healthy cells but, when cancerous, instruct tumor cells to invade surrounding tissues.

Although she started out as a basic scientist, eager to decipher cells’ conversations and figure out how their wires might get crossed to cause disease, Dr. Cress found herself hoping to translate her findings into better treatments for cancer patients.

Taking it to the Next Level

Translational scientists spin off basic scientific discoveries into goal-oriented projects, such as new drugs, technological advances or updated health recommendations.

“There are a couple reasons you get into science. One is curiosity. Another is you genuinely want to help people,” Michael D.L. Johnson, PhD, said. “If I can say that I saved somebody’s life with my research, that’s a really awesome feeling. That’s exactly what I’m in this career to do. It is really rewarding to have something that you discovered, something that no one else has done except for you, all of a sudden be out there to help people.”

The Medical Scientist Training Program at the College of Medicine – Tucson and the Clinical Translational Sciences Graduate Program at the College of Medicine – Phoenix prepare students to straddle the lab and the clinic. They receive mentorship from basic scientists and physicians, learning to translate lab findings to tomorrow’s treatments, and are awarded dual MD and PhD degrees upon graduation. Dr. Cress says mentoring these students is one of the most rewarding aspects of her work.

“Clinical colleagues know the clinical aspects and I know the basic science, but we need the go-between, somebody who’s got feet in both worlds. MD/PhD students are the bridge that brings it together,” Dr. Cress said. “They not only understand the basic sciences, they understand the way to translate it. There’s a special niche in the medical world for people like that.”

Melissa Herbst-Kralovetz, PhD, associate professor of Basic Medical Sciences and Obstetrics and Gynecology at the College of Medicine – Phoenix and director of the Women’s Health Research Program, is fascinated by the complex interactions between the microbes inhabiting the female reproductive tract. She connects with physician-scientists to translate her discoveries for the benefit of patients, and is collaborating with Dana Chase, MD, assistant professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, to develop a noninvasive method for detecting cervical abnormalities, including cancer.

“Because I’m a basic scientist, but also work closely with my clinical collaborators and with clinical specimens, I really do bridge that gap,” Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz said. “I work hard with clinical collaborators to maximize the translational impact. For most scientists, seeing your basic science translated is the most rewarding part. It’s exhilarating.”

Reaping the Benefits

The public saw translational science in action when the first COVID-19 vaccines rolled out. The technology behind them had been in development for years, built on a solid foundation of basic science.

“Vaccine development is a challenging landscape to navigate. Seeing a scientific concept go from clinical trials to being put into people’s arms in less than a year is just mind boggling to me,” said Dr. Herbst-Kralovetz, who is also a member of the BIO5 Institute. “People think, ‘Oh, that was this miracle solution that just occurred.’ No, there’s tons of research that went into that. There’s no way that could have happened if they didn’t have all those years of basic science to support that novel vaccine technology. That’s not something that could have been created out of thin air.”

On the flip side are people who might not trust a vaccine that seemingly appeared out of thin air.

“You have people saying, ‘Oh, they made it too fast,’ but most people have little understanding of how a vaccine is made,” said Dr. Johnson, also a member of BIO5. “We didn’t have to start from scratch. We knew how mRNA vaccines work. We knew how coronaviruses work. We had templates to apply to this situation. All those materials were there.”

Scaling the Mountain

One of her drug candidates is currently in clinical trials for multiple myeloma and lymphoma. Although she’s on the board for the startup company that arose from her drug candidate, she says she’s not too involved in the day-to-day process of pushing it through clinical trials.

“I hand it off to them, but I don’t do all the nitty gritty. Those are the people who are going to carry it forward. I’m onto the next thing,” she said. “I’m just happy I was able to contribute something, and that this contribution will lead to bigger and better things. It’s a dream to see it go to fruition.”

Whether they’re in the lab unraveling biology’s secrets or directing a clinical trial investigating tomorrow’s standard treatments, scientists are driven by a desire to push knowledge forward.

“Every day I get inspired by new discoveries. You see things that no one has seen before, and that’s awesome,” Dr. Cress said. “We’re like explorers climbing a high mountain. You’re able to see over the ridge, and nobody else has seen over that ridge before. There’s nothing like it.”

Media Contact:

Anna Christensen

520-626-7383

achristensen@arizona.edu

This story was originally featured in U of A Health Sciences Connect. All photos were courtesy of U of A Health Sciences.

About the College

Founded in 2007, the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix inspires and trains exemplary physicians, scientists and leaders to advance its core missions in education, research, clinical care and service to communities across Arizona. The college’s strength lies in our collaborations and partnerships with clinical affiliates, community organizations and industry sponsors. With our primary affiliate, Banner Health, we are recognized as the premier academic medical center in Phoenix. As an anchor institution of the Phoenix Bioscience Core, the college is home to signature research programs in neurosciences, cardiopulmonary diseases, immunology, informatics and metabolism. These focus areas uniquely position us to drive biomedical research and bolster economic development in the region.

As an urban institution with strong roots in rural and tribal health, the college has graduated more than 1,000 physicians and matriculates 130 students each year. Greater than 60% of matriculating students are from Arizona and many continue training at our GME sponsored residency programs, ultimately pursuing local academic and community-based opportunities. While our traditional four-year program continues to thrive, we will launch our recently approved accelerated three-year medical student curriculum with exclusive focus on primary care. This program is designed to further enhance workforce retention needs across Arizona.

The college has embarked on our strategic plan for 2025 to 2030. Learn more.