Research Symposium Addresses Latest Findings and Questions in Genomic Medicine

Experts in genomic medicine gathered on Nov. 20 to address the complex question: “Is My Fate in My Genes?” The second annual research symposium at the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix featured local and national experts who presented their latest findings in the areas of genomics and genetics, gene-environment interactions, as well as social and ethical considerations.

About 200 members from the community attended the free event, which discussed the role of genomics in diseases such as cardiovascular, cancer and neurosciences. The symposium explored the interaction of genetic medicine with environmental modifiers, including socio-economic factors, geographic environment, aging, diet and others.

“We are so excited to be meeting again for our second annual ‘reimagine Health Symposium, Is My Fate in My Genes?’” said Paul Boehmer, PhD, interim associate dean of Research. “This is a very intriguing, contemporary question to pose, and we have a line-up of expert speakers in a variety of sessions to address this topic and its different aspects.”

“The human genome was completed in 2003,” Dr. Wise said. “Since then, a lot of progress has been made in genomic medicine. We are now seeing cases where there is clinical utility and insurance companies willing to pick up genomic testing, because they see it being a benefit to the patient. It provides the opportunity for more rapid diagnosis, gets them to care and treatment faster and ends up costing less in terms of people’s time and the system itself.

“Although we have some really incredible stories that get told in the media around individual cases having remarkable recoveries due to genomic medicine, it’s going to take some time until this is something that any person can walk into their doctor’s office, expect to get sequenced and use that for the rest of their life.”

Experts presented on various topics throughout the day, which were broken up into three categories: Genomics and genetics, gene-environment interactions, as well as social and ethical considerations.

Genomics and Genetics

Experts discussed the power of genetics in cancer treatments, heart disease and developmental brain disorders. Presentations included Joann Sweasy, PhD, interim director of the U of A Cancer Center; Linda Restifo, MD, PhD, a professor of neurology, neuroscience and cellular and molecular medicine; and Robert Roberts, MD, professor of medicine and director of Cardiovascular Genomic and Genetics at Dignity Health St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center.

In 2007, Dr. Roberts’ team and a group in Iceland independently identified the first gene related to CAD, 9p21. About 12 years later, researchers have now identified 200 genetic variants. The gene 9p21 is very common, with about 75 percent of the population having this gene.

“A single copy of 9p21 increases your risk of CAD by 25 percent, but this is a relative risk,” Dr. Roberts said. “The absolute risk is less than one percent.”

According to Dr. Roberts, your genetic risk is related to the number of genetic variants you have associated with heart disease. Although these genetic risks increase your chance of heart disease, you can decrease your risk of dying from heart disease by 40 percent by maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

“It has been said for a long time that this should be the last century of CAD,” Dr. Roberts said. “Whether that is possible or not, I think it’s fair to think that heart disease at the end of this century is not going to be the number one cause of death in the world.”

Gene-Environment Interactions

Experts discussed both the genetic and environmental influences to tackling cancer and cerebral palsy and understanding a healthy aging brain. Speakers included Melissa Herbst-Kralovetz, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Basic Medical Sciences; Michael Kruer, MD, an associate professor of Neurology, and Matt Huentelman, PhD, a professor of Neurogenomics Division at the Translational Genomics Research Institute.

Dr. Kruer said that families are typically told these days that their risk of having another child with cerebral palsy is about one percent. In many cases, that’s true, but it depends on the cause of that child’s cerebral palsy. As their results have started to indicate, depending upon the nature of the genetic mutation for what is presented, the recurrence risk could be exponentially higher.

“Ultimately, we think genomics will provide a new window into cerebral palsy and neurobiology,” Dr. Kruer said. “We think that the genes that we are identifying will change the way we diagnosis patients and help provide new insights into mechanisms. In the near future, we think that this will allow us to better apply the treatments that do exist and really, we hope this will allow us to develop new therapies not just focused on the symptoms, but the cause of these developmental disorders.”

Social and Ethical Considerations

Discussions focused on health inequities, genetic counseling and ethical challenges of genomic medicine. Presenters included Joia Crear-Perry, MD, president of the National Birth Equity Collaborative; Paul Harmatz, MD, professor in residence at the University of California, San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospital; and Dee Quinn, MS, director of the U of A Counseling Graduate Program.

Quinn, who is a board-certified genetic counselor, discussed the process of genetic counseling and the importance of communicating risks for complex issues.

Genetic counseling integrates the interpretation of family and medical histories to assess the chance of disease and promote informed choices about risk and condition. It typically involves a team that provides services to a wide variety of individuals in different points of their life, including preconception and prenatal counseling, pediatric counseling, cancer, cardiovascular disease, neurology, research and industry. Genetic counseling as a profession is relatively new. It started in 1971 and now has more than 5,000 genetic counselors with 50 programs across the country.

Quinn added that she is concerned with direct to consumer testing and how people interpret those results. For example, she is concerned that if an individual gets a negative result for a particular gene, do they think they are now immune from it?

“What about people who get a negative result for breast cancer?” Quinn said. “Do they think they are not going to get it now? One-in-ten will get breast cancer and a subset of those individuals might have an even higher risk, because they had genetic changes that were not tested for.”

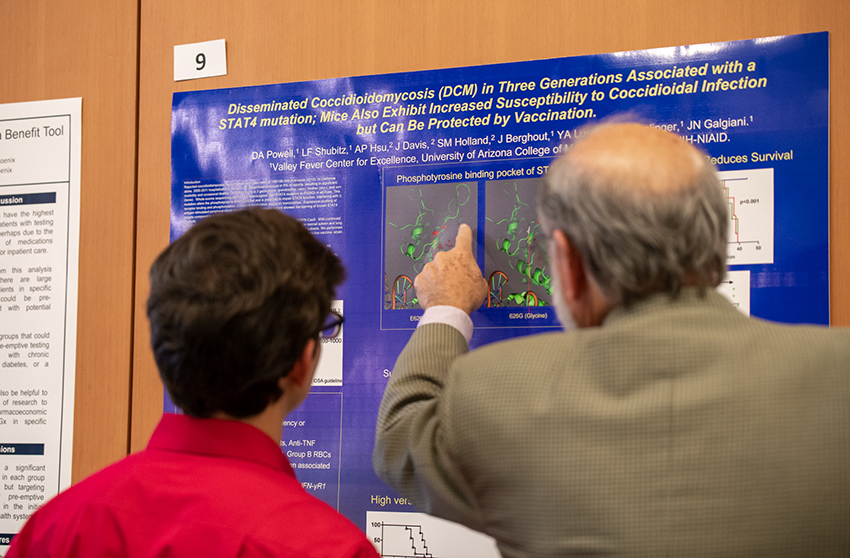

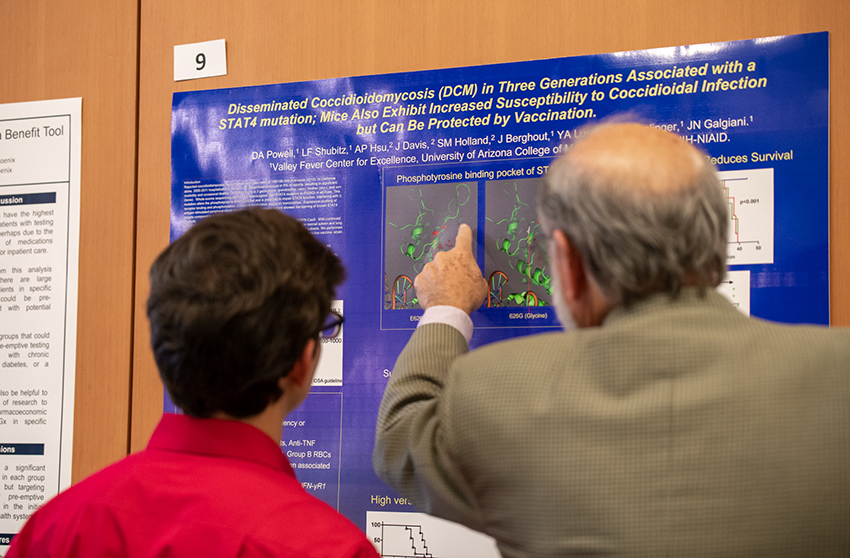

The event concluded with a panel discussion from experts who presented throughout the day, a poster session and networking event.

The symposium was made possible through the support of event sponsors including the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix Research Office, the Arizona Department of Health Services, and the Flinn Foundation.

About the College

Founded in 2007, the University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix inspires and trains exemplary physicians, scientists and leaders to advance its core missions in education, research, clinical care and service to communities across Arizona. The college’s strength lies in our collaborations and partnerships with clinical affiliates, community organizations and industry sponsors. With our primary affiliate, Banner Health, we are recognized as the premier academic medical center in Phoenix. As an anchor institution of the Phoenix Bioscience Core, the college is home to signature research programs in neurosciences, cardiopulmonary diseases, immunology, informatics and metabolism. These focus areas uniquely position us to drive biomedical research and bolster economic development in the region.

As an urban institution with strong roots in rural and tribal health, the college has graduated more than 1,000 physicians and matriculates 130 students each year. Greater than 60% of matriculating students are from Arizona and many continue training at our GME sponsored residency programs, ultimately pursuing local academic and community-based opportunities. While our traditional four-year program continues to thrive, we will launch our recently approved accelerated three-year medical student curriculum with exclusive focus on primary care. This program is designed to further enhance workforce retention needs across Arizona.

The college has embarked on our strategic plan for 2025 to 2030. Learn more.